As we set out on an adventure I had dreamed about, racing 5000km across the Atlantic Ocean in a tiny rowing boat, everything was going to plan…

On day two, my mate (Kevin Biggar) and I faced unexpected adversity. We found ourselves in the middle of a major storm. Headwinds, waves and currents – all trying to push us back to the start line in the Canary Islands. With our progress stalled we faced a choice. Put out a sea anchor, which would reduce the rate at which we would be pushed backwards, but at least we would conserve precious energy.

Or, keep rowing.

We took the tough decision and kept rowing. We adapted our shift pattern and worked together. We had no idea what the other 16 crews in the race were doing.

For 40 hours we rowed, and rowed, and rowed, but travelled less than half a mile across the ocean. Tired and disheartened, finally the storm passed over us, and we made the call to our support team by satellite phone.

“Whatever you’ve been doing, keep doing it” they said. “Everyone else has gone backwards [they all put out their sea anchor], and you are now 30 miles in front!”

Forty days later, we crossed the finish line in Barbados, winning in world record time. Our winning margin? Just over 30 miles! Might this story of adventure on the high seas offer some lessons for anyone going through a challenge? I think so.

How we cope with times of adversity, deal with ambiguity, and encourage innovative thinking can create an ultimate and sustainable competitive edge. It isn’t just bloody-mindedness. Rather, success is the result of stretching ourselves, thinking the options through analytically, backing our judgment, adapting our processes, and believing in our ability.

Here are five lessons from rowing through that storm with Kevin that are relevant to us all.

#1: The language we use changes how we think, then how we behave

In psychology, one of the most common styles of dysfunctional thinking is ‘catastrophising’ — when you take whatever’s happening, imagine the worst case scenario, then worry yourself into a frenzy about it BEFORE it has happened.

If you have a tendency to do this, give yourself a break, it’s super-common. But it’s also extremely unhelpful and can be a trigger or maintaining factor for depression and anxiety — and perhaps a desire to buy toilet paper during the lockdowns! Keep in mind that even if you do ever run out, toilet paper hasn’t always existed, and there are alternatives. Ancient romans used a communal ‘gompf stick’ – a piece of sponge tied to the end of a stick to clean yourself! 🙂

#2: CHOOSE your response, rather than behave as though changes are happening TO YOU

There are events in our lives we can’t change, but we can change our response to them that will fundamentally affect the outcome. Who would have thought ONE conversation Kevin and I had on day two of the race could decide the result six weeks later?

Your reactions are contagious.

For example, COVID-19 may never come into your home but your responses to changes are already there, and anxiety is easily passed on. Think about the people around you, especially if you’re a parent. You don’t want to train your kids to be easily scared, led by their feelings, and have an every-person-for-themselves attitude. You’re allowed to have, and express, feelings but base your words on facts and truth. In the words of Gandhi, “Be the change you want to see in the world”, even if you have to pretend for a while.

Structure your days — fall in love with a list.

There can’t be many things more motivating than a sense of progress. On the ocean we had map with milestones to cross off. I’ll talk about this more next time, but before you go to bed, write a list of what you’re going to do the next day. And after you get dressed each morning, make your bed! It’s the easiest way to prove to yourself that you can complete a task.

#3: Sometimes when you think you’re making the least progress, you’re actually making the most

We started the race with incredibly high expectations of ourselves, with previous races setting the benchmark for peak performance. The storm on day two could have been the end of our campaign – and my hopes of becoming a career adventurer. It turned out, though, that the lesson from that storm informed how we’d behave when another storm hit us on day 32.

Did the other crews find out we kept rowing after day two? Absolutely. Did those same crews put out their sea anchor again on day 32? You guessed it, yep!

#4: Our relationships last far longer than the storm

Kevin and I are different in so many ways, but we knew our performance (boat speed) was directly linked to our individual and shared wellbeing (some might call it ‘engagement’).

We committed to showing compassion, empathy and understanding from the outset. Doing this when you’re tired and frustrated isn’t easy, so we agreed some simple techniques to keep moral high. For example, if I was ever angry with Kevin I had to tell him, but only by speaking in a foreign accent! For the record, mine was German. Fun games like this mitigated the risk an ego-war on a tiny boat mid-ocean.

At a conference recently a woman told me she and her husband had a technique for conflict too.

“Whenever we have an argument at home, we have to start taking our own clothes off. Eventually it just gets weird and the argument ends”.

Kevin and I didn’t do that.

Hopefully, the goodwill you spread now will last longer than the challenge that’s in front of you. And if you’re struggling yourself, reach out. You’ll be surprised how you’ll be helping others by doing so.

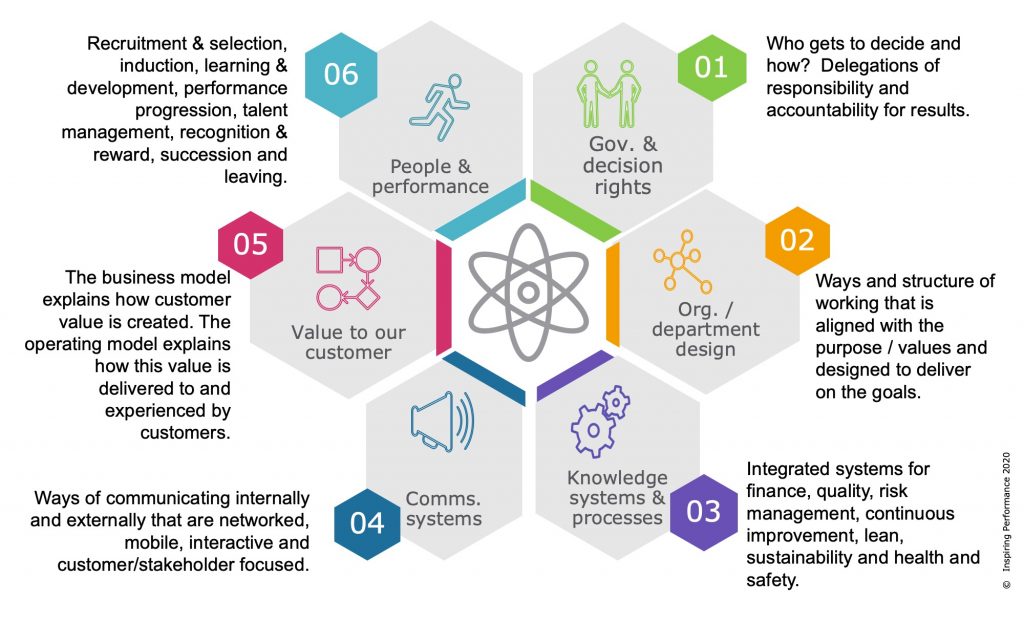

#5: Be deliberate with your operating model in the storm

An operating model is ‘how’ an organisation works as it pursues its purpose and goals. For us on the boat, that meant things like:

- The shift pattern of rowing vs. rest;

- Communication with media;

- Navigation and technology;

- Monitoring our performance; and,

- What each of us were responsible for.

During the storm, and once we decided we’d keep rowing, all these things needed to adjust. The point is, we were deliberate with what our target operating model needed to be.

Here’s what I’d consider to be the elements of an operating model for an organisation. Make sure your enterprise has clarity and alignment for each.

So, here’s my final message. Tell yourself that your responses to challenges are your decision. Will you put out the sea anchor, or keep rowing?

Jamie Fitzgerald is a Kiwi adventurer & CEO of Inspiring Performance – A company committed to helping aspirational teams, organisations & government agencies be the best they can be by having clarity & alignment on their purpose, strategy & how they’ll maintain momentum.

See all posts